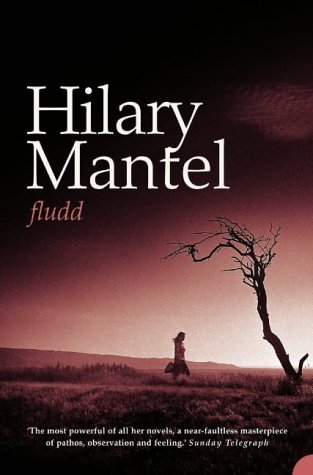

FLUDD

- HILARY MANTEL

I used to live in Budleigh Salterton which is where Hilary Mantel

lives, and she was my neighbour. Budleigh, in case anyone is unaware,

is the next town along the coast past Exmouth. Budleigh's such a

small town and news travels faster than a sigh. Everybody there wants

to know the next man's secret so every time we'd meet upon the street

we had to keep it like sister and brother. We'd wave to each other as

we didn't want all the world to know we were really lovers, so we'd

talk about the weather until we were alone together.

It's a strange place, actually, Budleigh. As with every small town

there's always gossip but that gossip never goes beyond its

boundaries. It's where Lady Di used to go when she was seeing James

Hewitt, presumably because they thought they wouldn't be bothered by

anyone there. And they were right. Everyone who saw them walking

along the beach knew who they were but they never caused a fuss or

said anything.

When Hilary Mantel moved there, it was just after her winning the Man

Booker Prize so anyone who knew anything about books knew exactly who

she was but again, no-one caused a fuss. I certainly didn't, anyway.

What first caught my attention about her was when she said in an

interview that she didn't have a bohemian bone in her body and I

thought this quite interesting. Most people I knew who possessed a

so-called 'awareness' were always steeped in so-called bohemian

culture and there was never any surprise when I'd peruse their book

shelves or rifle through their record collection. We all seemed to

have read the same books and liked the same kind of music. It was all

a bit boring, really. I mean, I don't want all people to be the same

as me and to share my tastes. If that was what I wanted then I'd join

the Jehovah Witnesses.

With her winning the Man Booker, Hilary's fame suddenly grew and then

for some inexplicable reason she became a hate figure for the Daily

Mail. Following a speech she gave regarding the royals and Kate

Middleton, the Mail took a few lines from what was quite a long talk

and twisted them out of context, in the process turning her words

into a 'venomous attack'. The on-line bile then unleashed by readers

of the Mail, the Telegraph and even the Independent was astonishing,

ending up with even David Cameron and Ed Miliband joining in with the

condemnation.

Bruised but unbowed, Hilary stood her ground and replied that she had

nothing to apologise for. With the publication of her collection of

short stories going under the title The Assassination Of Margaret

Thatcher, she induced further near apoplexy in Tory MPs and the Daily

Mail again who subsequently accused her of being warped, perverted,

sick and deranged; with one old Tory gimp even suggesting she should

be investigated by the police. Can you imagine? Investigated for

imagining the assassination of somebody already dead? Only in the

mind of a Tory fool could such an absurdity blossom.

The amusing thing about all of this is that Hilary Mantel is a really

intelligent writer and to see her being criticised and attacked by

those who also profess to write - as in the columnists and hacks at

the Daily Mail - makes for high comedy. It's like charlatans in fear

of the genuine article who make further fools of themselves by

pulling down their pants and waving their rudimentary scribbles

about, as though they had something to be proud of when in fact they

have everything to be embarrassed about. They are lightweights under

the impression that their views count for something when in fact

they're simply relics of a past now fossilised and obsolete, who

wither away on the vine of conservatism whilst those they are scared

of (immigrants, single mothers, the unemployed, chavs, Hilary Mantel

- the list is actually endless) move into the future.

As a writer, Hilary is probably perceived nowadays as a purveyor of

weighty, historical tomes but this isn't the only string to her bow,

her novel Fludd being a good example to highlight, it being a

strange brew of comedy, magical realism, and Christian eccentricity.

First published in 1989, it centres around a make-believe village in

the North of England in the 1950s where the Church and religion are

still dominant forces in people's lives though where everyone has

theological misgivings, grave concerns and doubts, not least of all

the local vicar himself. Following an order from the bishop that

various statues be removed from the church so as to focus the minds

of parishioners upon God rather than saints, a stranger arrives who

is taken to be an envoy of said bishop. He is, however, not all he

would seem and though it's never made clear, he could well be an

angel, a devil or possibly an alchemist.

Much fun and mischief is had in playing with the themes of religious

ridiculousness and the thankless task of presiding over a diocese of

what is termed 'simple people'. At times - for the first half of the

book, in fact - it reads like an episode of Father Ted, which seeing

as it's written by Hilary Mantel makes it all doubly amusing.

I don't think Hilary gets the balance quite right throughout the

whole book and you do tend to wonder at times where she's going with

her story but in the end it does all make sense. It also makes you

think; particularly when profound thought is drawn from the most

basic theological ponderings. There's a fair bit of symbolism going

on and a constant swing between reality and unreality, ending up in a

space somewhere between the two. For all that, it's still a very good

book and another fine example of beautiful, intelligent writing.

In the good sense of it (if there can be any other?), Hilary Mantel

is a classic, English eccentric who in her own quiet way is also

rather brave. Whether that's by accident or design is beside the

point. Anyone or anything that provokes the ire of the Daily Mail

must be doing something right. A curious thing also: in Budleigh

Salterton there's a lot of money. It's not only rich people there, of

course, but in certain parts of it there's a lot of wealth on display

and subsequently it leans heavily into Conservative politics. In such

a setting - as to be expected - there's also a fair few Daily Mail

and Telegraph readers and what all these people think of Hilary is

anyone's guess? What they make of the Daily Mail and its editorial

opinions in the context of it's attacks upon Hilary is also open to questioning, as is also Hilary's view of the

Mail nowadays?

Next time we meet (like sister and brother) I'll have to ask her.

John Serpico